David Grubbs

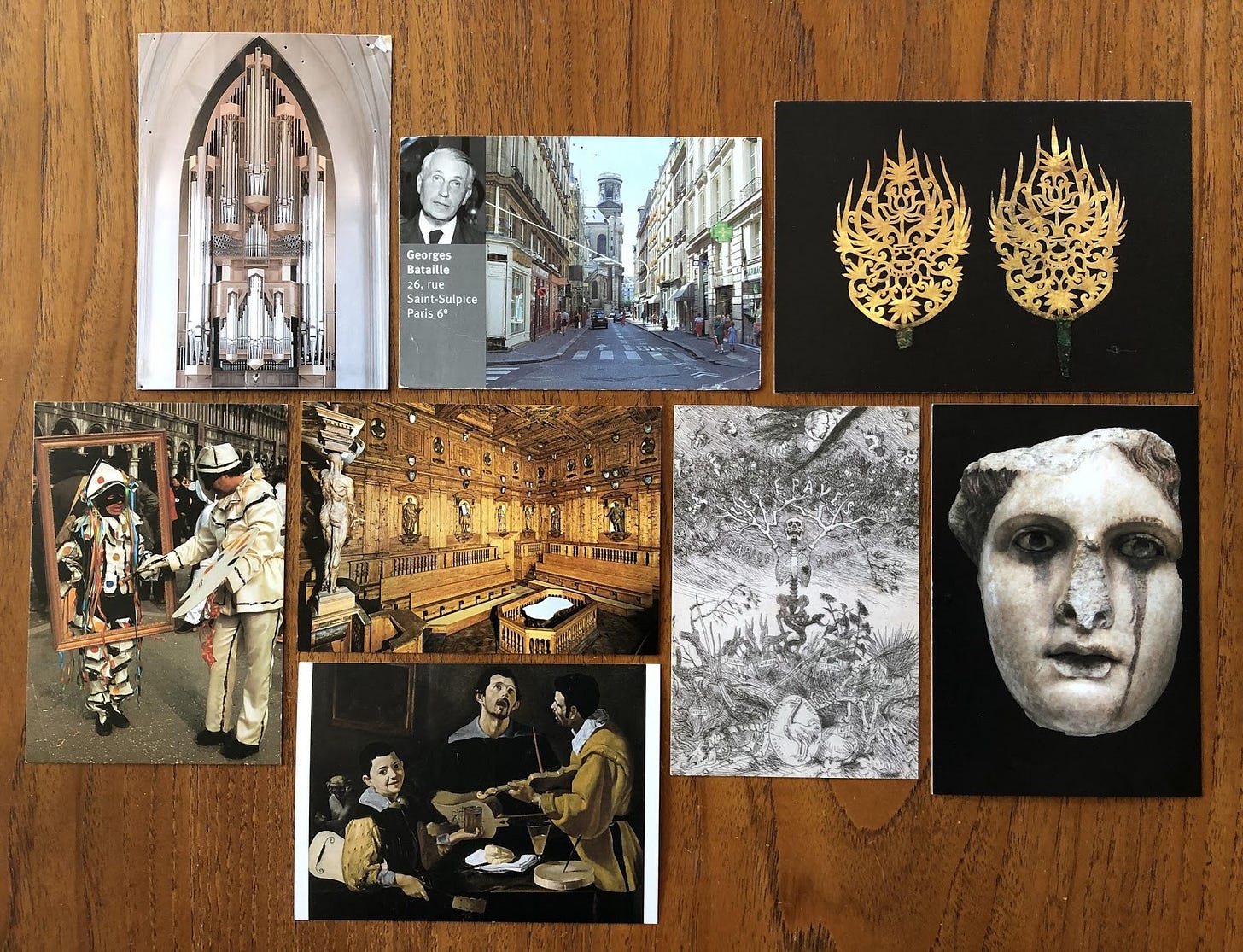

(Photo by David Grubbs of postcards he sent to his readers. “For the book launch I offered to send a chatty—or gossipy, if desired—postcard from my personal collection to anyone purchasing a book from Greenlight Bookstore, and this is a portion of the cards that I sent out.”)

David Grubbs has been performing live and releasing records for 35 years. He started in the Eighties as a teenager in a Louisville band called Squirrel Bait and moved on from there. How far did he move? In 2017, Dave Grohl covered a Squirrel Bait song live and said the band changed his life. One melodic rock band covering another, except that the founding member of the first melodic rock band left that mode behind nearly 30 years prior. And where did he end up? A few months ago, Grubbs led an ensemble performance of Luc Ferrari’s “Et tournent les sons dans la garrigue,” which was presented by INA GRM at a venue in Paris called CENTQUATRE. (Caps theirs, not mine.) The short film below documents the show, as well as Grubbs talking about the experience.

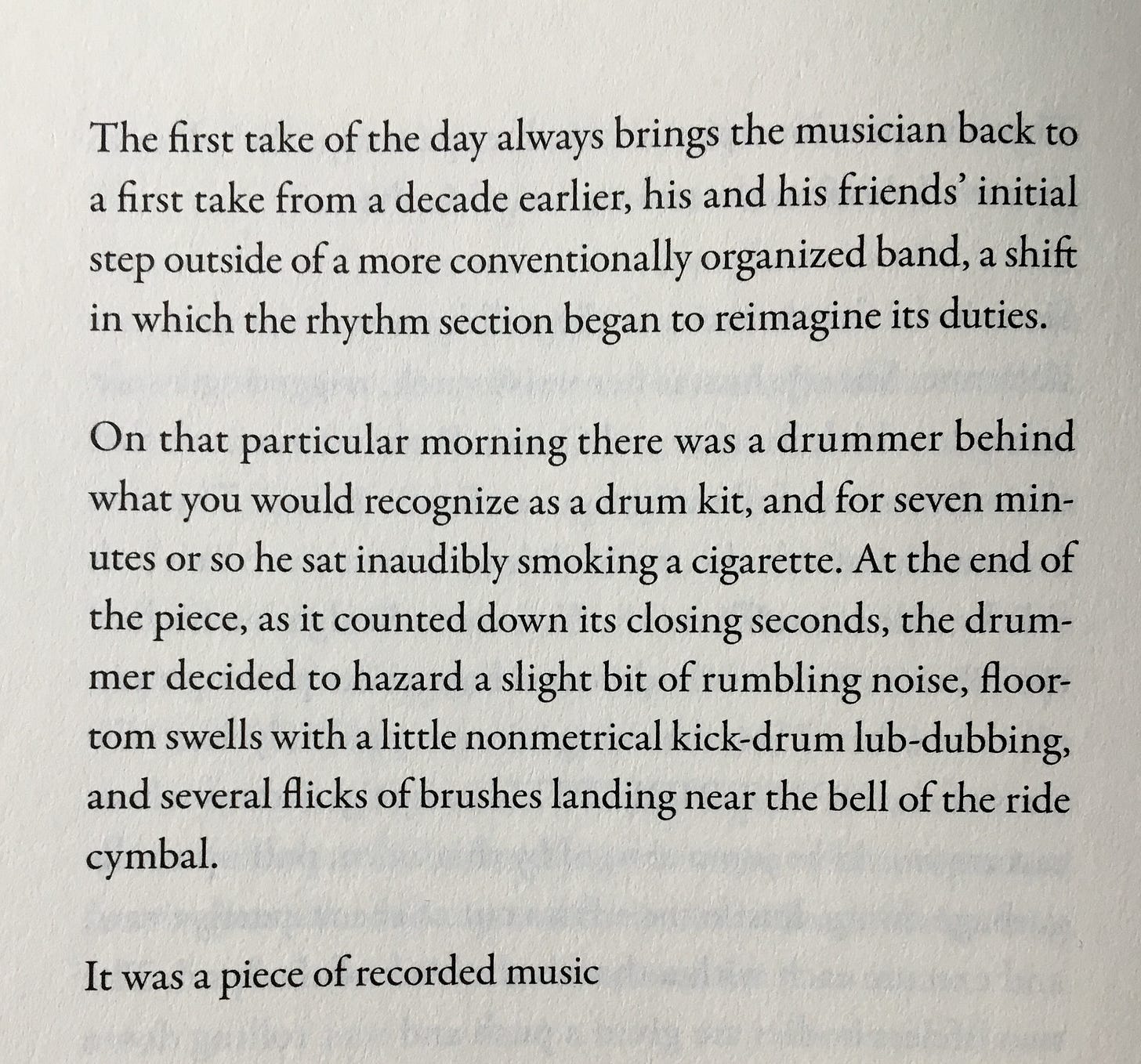

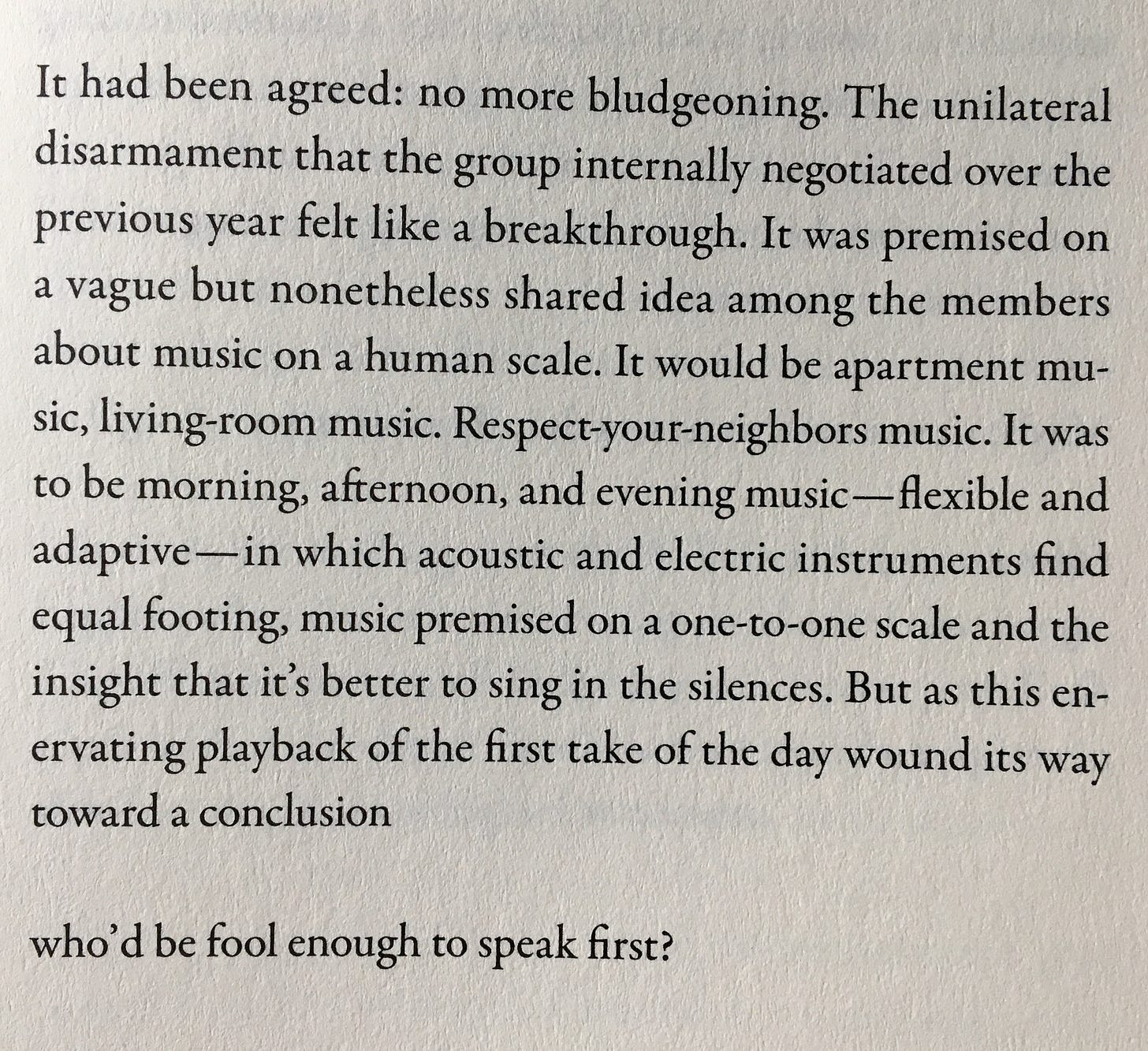

I love Dave Grohl. I am contrasting Foo Fighters and Luc Ferrari not to denigrate popular rock music but to suggest how vast the territory is when Grubbs is your Shackleton. One of the most important moments in the transition between the Eighties and Nineties, for live rock bands, was how much rock to leave behind. If you came up on cathartically loud guitar music, did you have to stay there? The answer from Grubbs, and a clutch of other musicians from Chicago, was absolutely not. Grubbs recently published his third book, The Voice in the Headphones, which he describes as “an experiment in music writing in the form of a book-length poem.” He sent me two excerpts from the book that speak directly to that loud/not loud pivot.

The excerpt below (p. 38) shares similarities with the recording session of the first Gastr del Sol record, The Serpentine Similar, and how strange it felt to commit, via the medium of recording, to Bastro morphing into Gastr del Sol. At that point, Gastr was exactly the same lineup as Bastro had been: John McEntire (smoking a cigarette behind the drums), Bundy, and me.

The excerpt below (p. 41) describes something akin to what Bastro had decided upon in becoming Gastr del Sol: “…no more bludgeoning. The unilateral disarmament that the group internally negotiated over the previous year felt like a breakthrough. It was premised on a vague but nonetheless shared idea among the members about music on a human scale. It would be apartment music, living-room music. Respect-your-neighbors music.”

The utterly fantastic record that Grubbs is releasing today, Comet Meta, is a living-room music album made with guitars, in collaboration with Japanese musician Taku Unami. How not loud are these guitars? You will find out below. My endorsement of this album, ideally, would disturb the neighbors.

Beyond the records and poems, Grubbs has become an important scholar in a loosely defined field that touches on poetry, sound art, and the American avant-garde. His first book, Records Ruin the Landscape, examines how artists like John Cage began complicating the idea of recording itself. Grubbs also teaches at Brooklyn College. It is there, with his day job, that we began.

SFJ: You were in the midst of teaching when lockdown hit. What do you teach?

DG: Three graduate seminars in three different MFA programs at Brooklyn College. One is a creative writing seminar called “The Sounded Word,” in which the only rule is that we have to listen to everything we discuss. We started with a recording of James Joyce reading Finnegans Wake. When lockdown started, we were talking about Jackson Mac Low and listening to recordings of Jackson Mac Low and Anne Tardos reading his work. Cecil Taylor came after that. There were seventeen students in the class, primarily poetry students and playwriting students. I’m also team-teaching the Thesis seminar in the Performance in Interactive Media Arts MFA program, which is an interdisciplinary performance program that I co-direct, and which I’ve taught in for fourteen years now. The third class is History of Popular Music and Technology, in the Sonic Arts MFA program.

In March, we were talking about the emergence of studios and labels and signature sounds in the 1960s. We read Peter Guralnick’s chapter on Stax Records from Sweet Soul Music and approached Stax Records as a kind of industrial model of making music, where everybody has a job. Isaac Hayes, for a couple of years, is on the songwriting team before he becomes a solo artist, because his voice is too beautiful to fit the Stax model of Sam and Dave and Otis Redding and people like that. We also talked about Aretha Franklin and James Brown’s Live at the Apollo.

For that class, I brought in this 1968 television documentary called Aretha Franklin: Close-Up. It’s really great. It’s just a thirty minute thing but it’s amazing because it’s very much about her music as gospel music. Either Aretha or her husband early on says something like, “You know, what Aretha does combines gospel and blues and R&B but it’s mostly gospel, you know, it’s only a little bit of the blues.”

SFJ: I love this film.

DG: There’s a great scene where Aretha is at the piano, working out an arrangement with everybody. Jerry Wexler is there, but he’s very modest, he’s not pulling rank on anybody. Aretha’s sister Caroline is there. She wrote the song and is one of the backup singers and choreographs the backup singers, and so she’s just hanging out, sagely tossing in suggestions about the arrangement. Aretha’s husband is there. It’s amazing that you don’t get the sense of a chain of command within the studio. It made me think about my perhaps overly simplistic heuristic model of Stax records as an industrial model of record production. You know, where you’re the songwriter, you’re the A&R person, you’re the engineer, you’re in the backing band. It probably wasn’t nearly as strict as that.

SFJ: These records have so many memories embedded in them, for most of us. Your first book, Records Ruin the Landscape, addresses how much we can attach to a recording and how that works for people like John Cage and Derek Bailey, who had a very complicated relationship to recordings.

DG: I think from reading the jacket copy, or the title of RRtL, people assumed that the book was a kind of puritanical screed against recordings when, actually, the texture of recordings is one of the great through-lines and adventures of my life. I’m just gathering information and trying to understand history. It’s this quixotic attempt to try to listen in the shoes of a given year, right? To listen to Isaac Hayes’s “Walk On By” as it as it might have sounded in 1969. It’s an imaginative reconstruction from the present moment. I was interested in relatively puritanical figures like Derek Bailey or John Cage because that was so alien to me. To be interested in the texture of time as it’s embodied in recordings is second nature to me.

SFJ: You mean that they would have objections to that appealing to you?

DG: That they would have had objections to it, or that they would have had no feeling for it. That’s almost even stranger to me. I understand working musicians having intellectual or ideological objections to recordings. I mean, Derek Bailey’s not so different from professional musicians in the 1920s feeling like radio was going to destroy live music. But I’m thinking of Cage’s extreme lack of sentimentality. He’s the least Proustian artist—he’s not interested in earlier time as it’s embedded in or represented by things like recordings. Sometimes Cage seems like one of the least sentimental artists ever. I wanted to think about that.

SFJ: How does that relate to your life as a musician?

DG: These things assume different importance based on how many records one makes, how much time one spends in the studio, and how many years one spends as a professional musician. I feel like I’ve been recalibrated a little because in the last year, I was playing a lot in The Underflow with Rob Mazurek and Mats Gustafsson, who are old friends. But I’m a college professor in addition to being a musician. I’ve got a number of professional gigs happening at the same time—they’re musicians who play a hundred gigs per year. That’s what they do. It’s fascinating to me to see how the headspace differs with somebody who does music exclusively. That’s their profession as opposed to, in my case, somebody who does different things.

SFJ: The Underflow has been playing live shows, right?

DG: We did a tour in January, eight nights in a row. The incredible thing about touring, particularly in Europe and in January of 2020, is that at the end of the night, you’re handed a flash drive with a multi-track recording of your ninety-minute improvised show. At the end of the tour, we had something like seven hours of really good recordings to go through.

SFJ: I was listening to the live Underflow record from last year and then, the next day, without trying to make this connection, I biked past the place on 13th Street where the Cat Club used to be. We saw Squirrel Bait there in 1986 or 1987. It was inspirational in terms of how extreme a band could sound. And now, that same person is in The Underflow. Perhaps an obvious contrast but it still gave me chills.

DG: That simultaneity is real. The nicest thing that anybody ever wrote about Squirrel Bait was when the records were reissued by Drag City. On the Other Music website we were described as “the greatest high school band of all time.” I thought, “Oh, that’s very nice for someone to say,” but my experience is that we were the second or third best high school band in Louisville, Kentucky.

DG: I was a late adopter to social media because I knew how much of my day it would likely take up, and kind of does. All of these different parts of my life, almost forty years of them, are more simultaneously present than ever, given the fact that nearly every day I receive notification that somebody posted a photo of a band that I was in thirty years ago, and also that now people rarely bemoan the fact that records are out of print. They can hear what music that I made when I was 17 years old sounds like, and they could hear what music that I made when I was 52 years old sounds like.

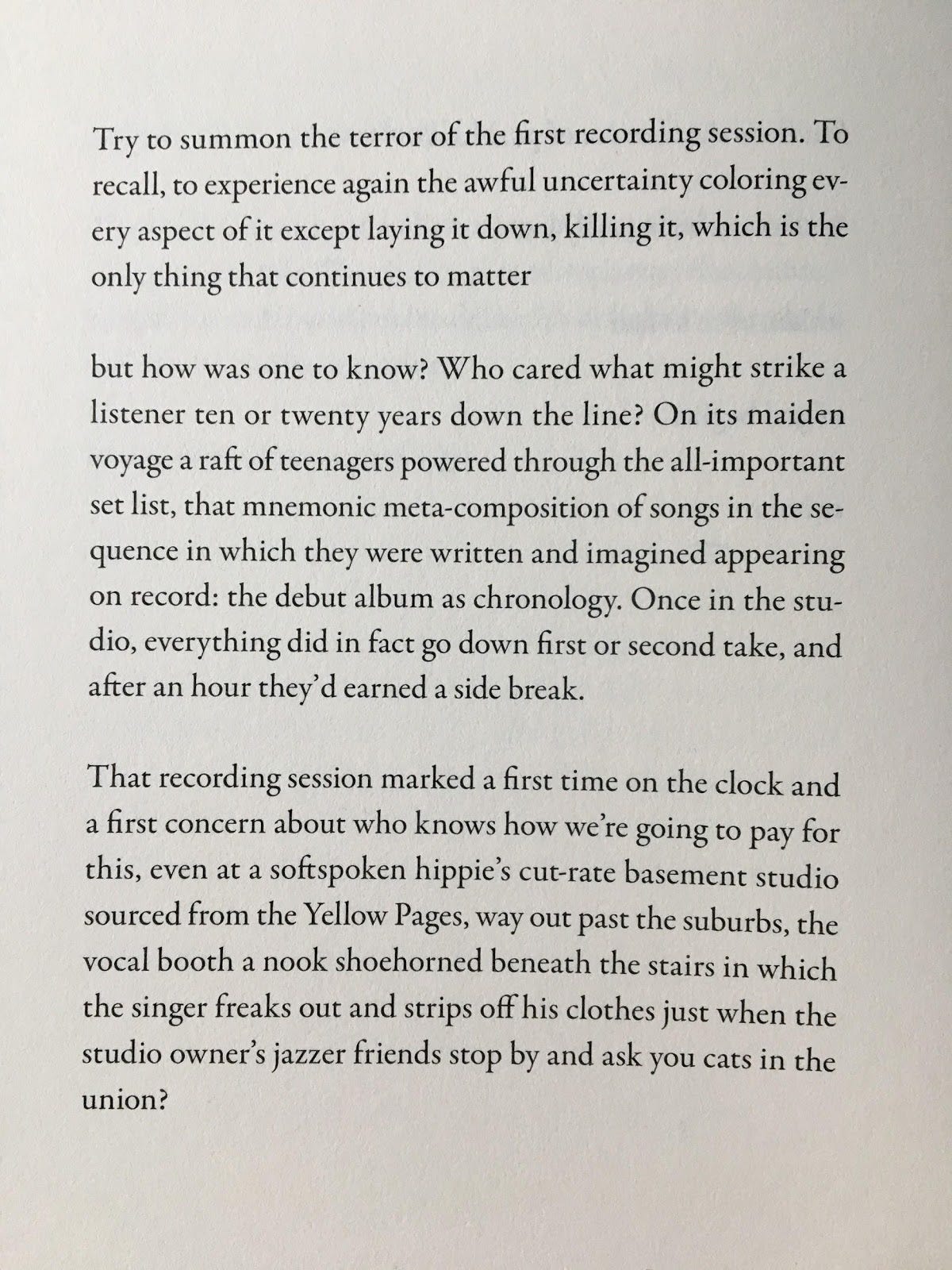

DG: The Voice in the Headphones, like Now that the audience is assembled, describes a single day of musical activity. The next book that I’m writing, which is I think the third and the final in the series of these books, concerns making music while on tour, and it spans thirty years. Although The Voice in the Headphones takes place over the course of one day, it’s more like thirty years of stuff is jammed in there. I had a sense that it would be set in every studio in which I’ve set foot. That’s not entirely the case, but there are a lot of different studios that elbowed their way in there. I’m looking for the one page in here that, for me, is a description of the very first Squirrel Bait recording session. Here it is.

SFJ: What has nobody noticed about this book yet, something you’re really proud of or which you feel is important?

DG: The book is so new—it was published at the outset of the pandemic, born in captivity, and the book launch took place via Zoom—that much of the feedback has come from friends, when I’ve found that the most exciting responses come from people whom you hardly know, and who weren’t privy to the process of the book’s writing. What hasn’t been noticed yet? The narrative gets derailed at a couple of points through long excurses into the fictional film for which the musician is creating a soundtrack. I’d be eager to hear what people make of those descriptions: the extent to which they add up to a coherent sense of this fictional film, or what their reference points for the film might be. I suppose at a more juvenile level I’m interested to see if anyone can figure out the song in the “name that tune” game that happens relatively early in the book—at lunchtime. There probably aren’t sufficiently many clues.

SFJ: Tell me about this record you made with Taku Unami, Comet Meta. It’s one of the best things you’ve ever done and also representative of almost everything you’ve done. Typical and unique, if that’s a valid category?

DG: The stuff with Taku—some of it we did on an airplane and some of it we recorded at a risographstudio in Tokyo, a D.I.Y. print shop, where you could play only at speaking voice volume. It’s in a quiet neighborhood in Tokyo and we played through amps that weren’t much bigger than my shoe. We were setting them at the most aspirationally modest volume and still being told, “Lower, lower, lower.”

You can hear “Comet Meta” at the top of this solo guitar performance I did in April.

DG: The Underflow recordings are really about being in the presence of an audience and what it’s like to be on stage. That stuff is super electrifying for me, because they’re just such phenomenal players. They’re total monsters. I can’t believe sometimes that I’m standing on the same stage with them. By contrast, Comet Meta feels more like an informal conversation, with all of the stoppings and doubling back and double-checking things and looking stuff up.

Taku is one of the funniest, driest, smartest, most inspiringly perverse persons you could ever have the good fortune to spend time with. I first met him more than twenty years ago in Tokyo and he’s been here a bunch to perform. The last time I saw him play in the U.S., he did a duo with Sean Meehan. His instrument was a DMX controller, six faders controlling the intensity of six different electrical fans at the Fridman Gallery. When all six fans were going, shit was flying everywhere. Not only was it cacophonous, but it was like a miniature storm inside the gallery. Comet Meta is distinct from that, beginning with the fact that for me it doesn’t seem predicated on a real-time, durational feel.

SFJ: How much of it was composed before you went in?

DG: Pretty much everything on Comet Meta is composed. It’s very much a studio assemblage. There’s no improvisation on it.

SFJ: There’s one Underflow record out?

DG: Currently there’s just one Underflow album, which was our first show. The next one will be a double LP on Blue Chopsticks called Instant Opaque Evening, drawn from four of the concerts this past January.

(DG: This is an unpublished photo of Taku and me at the Studio Ghibli Museum in Tokyo. Taku claimed that he won tickets at a convenience store. I'm not convinced that he didn't pay some exorbitant price for them.)

SFJ: How early on in your life did you figure out that you were going be a musician and an academic?

DG: When I was an undergraduate in college, I started thinking that I would be a college English professor and that would make it economically possible for me to make music. When when I was an undergrad, I was a tutor for a couple of years for college courses in a prison, the Lorton Reformatory in northern Virginia. That was kind of the best thing that I was involved in around that time. We discussed Dutchman, we discussed Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? We discussed their writing; everyone wanted to get better at writing. Teaching felt easy and rewarding.

I graduated from college and toured for the better part of a year. Then I started a master’s and then a PhD program in English. I assumed being a college professor and making music would be utterly separate pursuits. Occasionally I would joke like, “Oh yeah, I’ll probably wind up teaching college courses about punk rock, duh.” And lo and behold!

I’m really incredibly grateful that the two have come together. It happens! For instance, Drew Daniel is somebody I’ve known since I was in high school in Louisville. He’s an English professor at Johns Hopkins. And man, he works his ass off, being in Matmos and also being a scholar of Shakespeare and the English Renaissance. I get to teach classes about what it is that I’m listening to and reading in the present moment. And that dovetails with what I do as a musician and a writer.

SFJ: Where were you an undergraduate and a graduate?

DG: Georgetown University. I’m from Kentucky, so I have to say Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. so people don’t think I’m talking about Georgetown College in Georgetown, Kentucky. I went to the University of Chicago for grad school.

SFJ: That’s in the Eighties and Nineties?

DG: Yeah, I think we’re exactly the same age. I was in college from ‘85 to ‘89 and I started grad school in ‘90. At the University of Chicago, I think people were averaging 10 to 12 years for PhDs. I did my coursework in a timely fashion and took my exams. Then I thought about the dissertation, and did nothing about it for eight years. I was playing in Gastr del Sol and the Red Krayola and making solo records. For a number of years I was in extended research residency, which is the technical term for academic cryogenic suspension. I finished my PhD in 2005, fifteen years after I started grad school.

SFJ: Whoa.

DG: I did receive a complaint from one faculty member about my cavalier attitude toward finishing it. I did finish it, but only because I’d been offered a job at Brooklyn College as a visiting professor. It was a position that would turn into a full-time, tenure-track job if I had a terminal degree in hand within a year.

SFJ: Whatcha do?

DG: A PhD in English, and my dissertation was an early version of Records Ruin the Landscape: John Cage, the Sixties, and Sound Recording. When I was in grad school, my primary field in the comprehensive exams was 20th century American poetry, but the secondary field —and what I was more excited about in terms of classes that I’d taken—had to do with technology and representation.

SFJ: What’s different about academia now, or the way that you experience it?

DG: I attended private schools, and I don’t know what it would feel like to be teaching at a private institution right now. The historical mission of CUNY has always been that of access. The fact that its tuition is something like less than a fifth of most private schools is significant for me.

SFJ: Is there an upside of digital education right now? Or, if not, where might it be?

DG: The main thing that I’m struck by regarding that in the classroom is that given digital access and online access at a very surface level, everyone, including me, is tempted to act as if they know everything. People can namecheck an artist easily, or give a kind of Wikipedia-ish definition. But I learn alongside the students when people drop that pretense, myself as well, and listen deeply or commit the time to listening and reading. That’s one of the challenges in the classroom—modeling committed listening. “We’re going to listen to this thing for 25 minutes because we should listen to the entire piece.” Any way in which we can short-circuit time fragmentation is exceedingly helpful.