Kiera Mulhern

(Photograph by Leigh Ann Josephine.)

Kiera Mulhern’s Silt was an album I leaned on last year. It doesn’t make any obvious or insincere moves, and it remains generous without resolving or stabilizing. The first time I heard Silt, it felt like a hand was coming through the wall to grab my socks. The piece lasts thirty-two minutes, neither long nor short. There are roughly two elements—the human voice and the rest of it. Mulhern is a narrator without a story, here, reciting poetry, though not poems. Along with the voice you hear a clutch of musical sources: flute, Sidrassi, autoharp, and umpteen various files, both found and made. Though it’s an entirely digital production, the music—if that’s the right word—feels like something you’d find under a roll of unused sod. The pace and shaping is as confident as the individual sections, of which there seem to be six, each about five minutes long. (That’s my count, not a track listing.) The halfway stretch, from about 10:00 to 20:00, is a fertile haze that rises above most of what I heard in 2019.

There is an excerpt from Silt on Soundcloud. You’ll have to go here and buy the album to experience the whole of it. (And you should.) Kiera recently performed a fantastic new piece called Pillar Dweller, which you can listen to in its entirety here. Where Silt rises slowly, Pillar Dweller flings open the windows.

Over the last few months, Kiera and I’ve had a bunch of talks, some of which were as good as the music. I managed to lose the recording of our first actual interview because, of course I did. A few days ago, we reconstructed that conversation.

Pillar Dweller is new, yes?

Yeah, I performed it on January 31st at Montez Press Radio in Chinatown. It’s a half-hour live set and kind of also a product of grief.

Do you want to talk about the grief?

My mom died on January 6th. She had been sick for a long time, but it still came as a shock. I ended up preparing that set while I was just beginning to process the loss. A few days after she died, my sister and I had an aimless morning at my mom’s apartment and we ended up doing a sort of lament or meditation thing with some of my mom’s old wine glasses, where we sat across from one another with the glasses between us and played them with our fingers. We did it for a long time, just sitting there wordlessly with the sounds, and I felt in that moment like the death was being given its proper space and respect. I ended up doing that again in the beginning of the Montez Press set. Then there are sounds that are more chaotic and discontinuous, which is also what mourning is.

Let’s use my notes from the interview I lost, for now. “Choral mom. Poet. Crushed glass.”

My mom sang. She was a choral singer. I was probably trying to explain my relationship with harmony and pitch, which started with her. “Crushed glass” was about the music Jack Patterson and I worked on together a few years ago, the first time I tried putting poetry together with sound. One of our sources was the sound of crushed glass. Another was slowed-down cricket sounds.

“Machinery listen.”

I listen to machinery. There’s so much texture to sift through before you get to the harmony, but there’s always harmony. Going to sleep, I hear music in the air conditioner, when it’s on. Maybe everyone does.

It’s like Éliane Radigue hearing music in the helicopter rotors when she lived near the airport in Nice, in the ‘50s.

Her way of extracting melodies from things is amazing, or rendering things melodic that aren’t melodic at face value.

“Search terms, compositional process.”

I wrote the poems and then would reread them when I was on the train. I’d think about what physical worlds the words suggested. I kept a list of sounds to record or to look up, sounds that the poems would fit within. I searched Freesound and the BBC Archive.

“Ancient things.”

It feels as if things are in some sense drier now, or drier than they were in ancient humanity. Today, there’s more build-up of artifacts and less fertile soil to build life into, or out of. With Silt, I was thinking about a time when there was less dust and more moldable substance.

Multiple or moldable?

Moldable. I was thinking about the world when things were less solidified.

“Poems set before and after human time.”

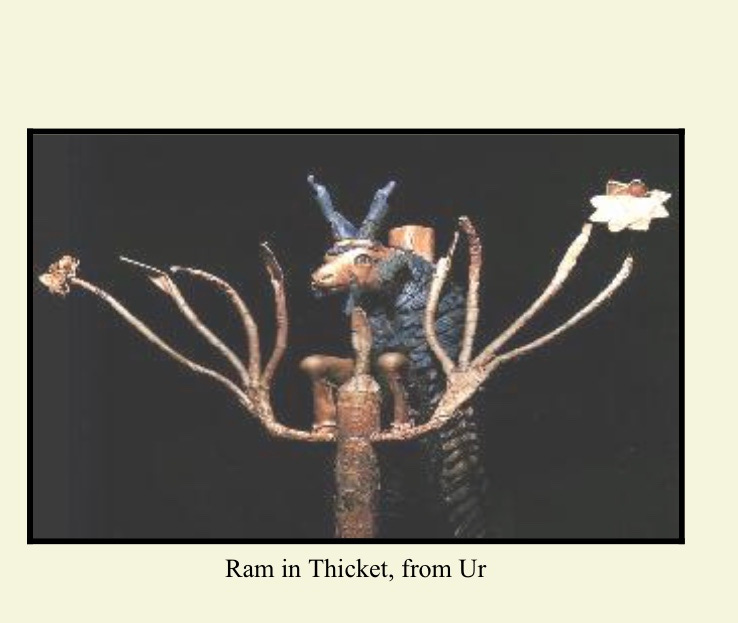

I started by thinking about something “after the apocalypse and before us, before human time.” I often want to examine things from a distance, like a detached observing eye. I was trying to be that eye when I thought about ancient Sumer. I was looking for a thread from there to here.

What’s up with Sumerian poems?

We’re pretty sure that writing was invented in ancient Sumer. We have these artifacts of that moment—the Sumerians inscribed their writing on slabs of clay, rather than paper, so a lot survived. The poems made me think about how our basic humanness seems to have changed very little across time. But also, the remains are fragments. So much is absent.

There are also Sumerian receipts, records of financial transactions that nobody meant to preserve. They’re just traces of the everyday, like if a W-2 form somehow lasted four thousand years. It’s beautiful because of what’s withheld. With a poem, you can grab onto some sort of emotional narrative and say, “Oh, these people, they were just like me.” But with something like a receipt, there’s so much missing context.

“Sour algae. Silt.”

Silt is the pliability, the non-dust, the opposite of the dust. Silt and mud and clay are all constantly invoked in Sumerian poetry. The poems seem to be aware of their own materiality.

“Destruction, beauty, artifact.”

I don’t want to neglect the beauty created by humans even now, even when they’re so destructive and clumsy. But I was interested in something sort of Edenic, and that’s how I came to choose Sumer as a pre-destructive place and time, but I don’t think that it’s all just garbage now. Maybe using the term Edenic is not really representative.

“Five minute sections.”

I made it in sections, each a few minutes long. I would finish a section and then find a way to stitch it into another one. You know, like songs. They’re songs. Sort of.

“Accusation of shrimp.” Nope. How about “connection of sounds”?

Right at the very beginning, you can hear a woodpecker pecking and a sheep baa-ing. A baa has tremolo, and it pulses at roughly the same speed that a woodpecker pecks. I tried to manipulate the waveforms to pair each pulse of a baa with each peck. These sounds have a similar sort of rhythm, but it’s barely rhythm. It’s somewhere between texture and rhythm.

“Tuning an organ.”

I found a recording of an organ being tuned. I’d take a section with a single note, layer it a bunch of times, and then shift the pitch of each layer, slightly, for flutter.

“Days were hoofing and each had big frame.” I am guessing here.

The days where heaven and earth had been fashioned. It’s from a Sumerian poem. It’s a line that I stole, and it’s in Silt.

“Hieroglyphs, simplified symbols, picture.”

Hieroglyphs existed but the Sumerians were the first ones to change how text was used. The text stopped looking like the thing that it was meant to represent. Text became abstract symbols, rather than visual representations of things.

Yeah, but the Sumerians were swallowed by the desert.

Totally.

How long did Silt take?

I spent the most time on transitions, much more than on each section. It took three or four months to make the whole thing. I was going to just upload it to my SoundCloud and release it that way, but then I decided to send it to a few labels, including Entr’acte.

“Clarice Lispector,” which is not confusing, and “ecstatic neutrality.” What a great phrase.

In The Passion According to G.H., there’s a scene where the narrator has a hallucination. She sees a desert that’s from thousands of years ago. Insects are moving in it, and the narrator talks about how the insects have an aliveness. It’s a thick, neutral aliveness, something unreachable by words or organized thought. That’s what I was trying to find in the realm of sound, in the clicking and gurgling. You know? The sound of swamps and empty plains. Empty only in the human sense, though. That kind of aliveness, for Lispector, is not about verve at all. It’s heavy and dense and hard to see. It’s like bugs.

But bugs are light.

Yeah, but not to themselves, not in their experience.

You’re talking about what bugs know?

They just know aliveness, I think. Like bugs know only aliveness and we know all this other bullshit.

You toured Silt, right, before you did Pillar Dweller?

Yeah. The shows were cute. I was lucky enough to be touring with Sydney Spann, one of my favorite people in the world, who performs as Sunatirene. We did sort of a funny format which I plan never to repeat, which was spending a couple months at our day jobs Monday to Thursday and then traveling and playing shows Friday through Sunday. This is a video from the show at the Anderson gallery in Richmond.

I’ve been interested in the combination of text and sound since I was a teenager, when I was writing plays. I’ve been uploading pieces of The Fork, a narrative piece I’ve been working on for a couple of years. (Only two of the ten sections are done.) Anyway, your work reminds me of ASMR videos and Robert Ashley’s Automatic Writing. That is a genius-ass record. Do you know it?

Yes, I love that album.

Automatic Writing was re-released last year, not long after Silt came out. If nothing else happens, I’ll be happy if everyone here buys Automatic Writing and Silt. But they don’t even have to buy Pillar Dweller! It’s just sitting there, for free. Tell me about ASMR and Ashley and then we’ll be done.

I’ve always been interested by the musicality of unsung speech, in the same way I’m drawn to the music of machines. Ashley also doesn’t distinguish entirely between speech and sounds and music. They were in many ways the same to him too, I think. In fourth grade, when I started learning to read music, I remember trying to figure out if we spoke words in ways that were possible to notate. I thought, “We must speak in musical notes.” This was before I understood that there are pitches in between what Western notation covers.

With ASMR, there’s close attention paid to the nature of spoken voice, probably more to timbre and amplitude than anything else. To be honest, I’m sort of repelled by it. It’s kind of masturbatory. But I like the aspect of closeness, intimacy with objects. I think the vocal aspect of ASMR is less connected to what I’m doing because it’s not my hope for the voice to be soothing in my work, which is my impression of how speech works in ASMR videos. Like, it’s there for pleasure or stimulation and not a whole lot else?

There’s an old mediation practice called incubation I learned about looking into different meanings of the word syrinx. It’s the name of one of my favorite Greek nymphs and of my favorite Debussy piece, so it seemed worth exploring. To incubate, you would lie down in a cave and drift off to half-sleep or half-aliveness, totally still, and let the world or spirit float into you. Parmenides was part of a group of healers who would practice incubation in caves. He talks about how, lying still in the cave, once you began to let your consciousness slide out of you, a sound would start to occur like whispers or snakes hissing or wind blowing in reeds or a faraway flute. This sound was “syrinx.” I feel like way before I read about it I was already drawn to this kind of sonic world, to caves and hiss and words that don’t clearly explain themselves.

Automatic Writing sounds like syrinx. There is something about that sound space, a quiet, close dryness happening inside a vast echoey wet world which you’re only vaguely aware of. That feels so incubatory, and it lends itself to Ashley’s interest in ego-surrender and letting involuntary actions surface. The way the voice drifts in and out of legibility in Automatic Writing also feels connected. There’s a lot of air in the speech in Automatic Writing, a lot of the syrinx texture. I tried to put it into Silt, too.