I wrote this for The Village Voice twenty-four years ago, and since it’s not available on the Voice website—though most of my pieces are—I’m posting it here. The piece was occasioned by the release of Arkology, a CD anthology that has since gone out of print.

There’s no one else with a history in Jamaican music like Hugh Rainford Perry, born in 1936. Roughly speaking, there are four major phases of his career: (1) 1963 to 1973: Perry interns with the legendary Coxsone Dodd, scouting talent like the Maytals, and helping record acts at Dodd’s Studio One as the music evolves from mento to ska to rock steady to reggae. Eventually falling out with Dodd, Perry goes on to work with rival producer Joe Gibbs, forming the first versions of his own Upsetters house band and starting the Upsetter label. Perry’s 1968 jab at Gibbs, “People Funny Boy,” slows down the beat of ska to create what Perry alleges is the beginning of reggae, but he’ll have to joust with Toots about that one.

(2) 1969 to 1978: Perry teams up with the pre-Island Bob Marley and the Wailers, recording some of the most staggering roots reggae ever. Aston and Carlton Barrett abandon the Upsetters to join the Wailers full-time on bass and drums and Perry begins to work with excellent vocalists like Junior Byles, the Congos, and the Meditations. With King Tubby, Perry helps create dub, which he stretches to the breaking point in the next phase.

(3) 1974 to 1979: Perry builds the Black Ark studio in the yard of his home in Washington Gardens, one of the most mythologized locations in popular music, variously accorded X-Files powers, invisible engineering attributes, and a palm tree with an audible heartbeat. Amid controversy, most of the Ark burns down in 1979 while Perry grows increasingly paranoid.

(4) 1980 to present: Records a hodgepodge of solo albums as a vocalist with various backing bands in New York, Kingston, New Jersey, London, and points elsewhere.

THINGS SCRATCH ALLEGEDLY DID: Take dumps in his own studio and arrange them symbolically; burn his studio down to scare off a German groupie; walk backward hitting the ground with a hammer for a week; place curses on various enemies; blow an advance from Island on an antique silver set from Cartier; worship bananas; eat money; baptize house guests with a garden hose.

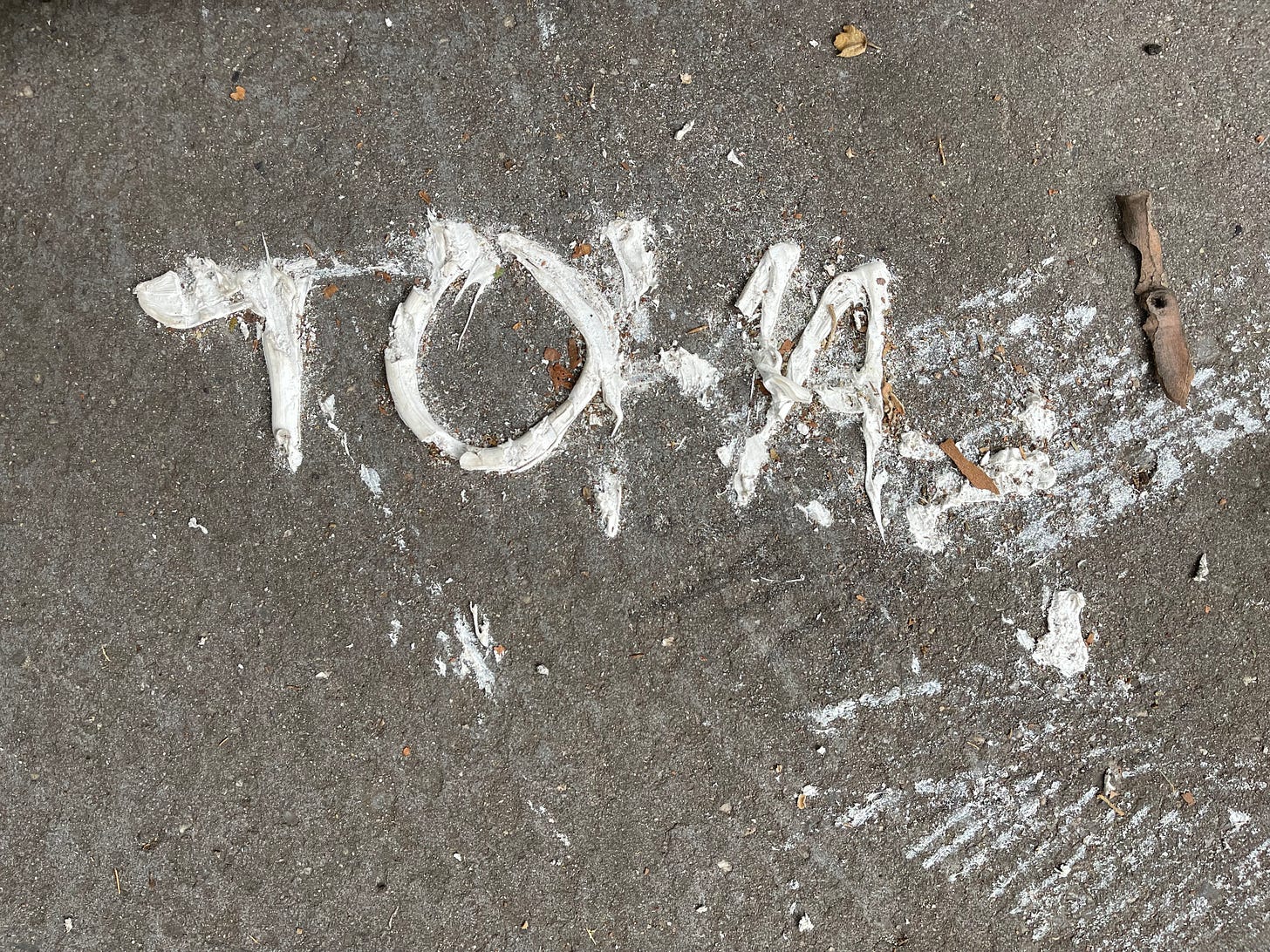

THINGS SCRATCH DEFINITELY DID AND DOES: Call himself Pipecock Jackxon Kimble, and The King of Mess; write all over every available surface of Black Ark; glue mirrors to his clothing; speak only in rhyme; call Chris Blackwell a vampire; build a duck pond inside the Black Ark studio; issue hectoring musical broadsides against onetime friends he decides have cheated him, including Prince Buster, Coxsone Dodd, Joe Gibbs, Bunny Lee, Chris Blackwell; quote the Bible liberally, changing key words that don’t fit; license the same tracks to multiple parties.

What makes Scratch so good, though, is his distortion of the reggae mise-en-scène. In a basically conservative genre, producer Perry’s anti-science science of intuition and quick hands injects chance, humor, and disaster without ever really leaving the pop song behind. Those who look to Perry’s shit-talking for a cosmology will get burned; those who dismiss his output because of his shit talking will miss the aurora borealis of reggae.

Perry’s achievements can’t be reduced to any particular approach to mixing or recording or writing. Taken together, what emerges is a physicality of sound, or rather a sound that establishes a physicality. I wouldn’t venture a guess as to whether his music is bringing us into Black Ark or taking us somewhere entirely beyond Earth, but his productions are tangible as much as they are audible. The aliveness of Perry’s music falls between the human and the vegetable, a growth that continues when the record is off.

Roast Fish Collie Weed & Corn Bread is credited solely to Perry as artist, and is one of my favorites. The tracks pit house-band rhythms against Perry’s pixie dust percussion and mixing-desk abuse, over which Scratch narrates like a bootleg Martha Stewart: how to stay healthy, how many lights are broken on his block, etc. His toasting is early rap, his dub strategies—like Jah Lion playing dominoes louder than Max Romeo’s singing on “Norman”—are closer to Stockhausen than King Tubby, and his uncredited cover versions of tunes like “Tell Me Something Good” and “Fever” made him a proto-Puffy. And it was all recorded at Black Ark with just a four-track quarter-inch TEAC reel-to-reel, 16-track Soundcraft board, Mutron phase, and Roland Space Echo. Bouncing tracks together to create 16-track thickness, albeit with considerable signal degradation and tape hiss, Perry bubbled more than pavement in July and was guided by voices that could actually sing.

Perry doesn’t compile easy because, like very Jamaican artist since 1964, he made umpteen records, most of them seven-inches he produced for the voracious, day-to-day music consumer. He’s made coherent albums when it mattered to him or when Island pressured him—Roast Fish and Super Ape are examples. But he’s done much of his work on the fly, and the lion’s share of that work has been for him to license and others to sequence and package. And Perry is still mortal: plenty of other Jamaican producers have more consistently heavy rhythm tracks, like Tubby or Burning Spear, and better-sounding records overall, like his mentor Coxsone Dodd.

Also, since Scratch spent most of his time producing, conceiving, and conjuring behind the boards, rather than politicking and selling, attributing specific tracks to him can be tricky. In the intense assembly line of Jamaican music making from 1966 to 1978, with tireless house bands, recycled backing tracks, and revolving engineers and singers, roles are not easily defined. Long before the sampler started eating up an existing recorded catalogue, Jamaican recording practices—five or 10 prereleases for every commercial release—cannibalized authorship before it was established. The weekly flood of 45s on Upsetters, Trojan, Black Art, Wild Flower, Orchid, Scandal, et al. doesn’t make an easy historical trail.

The three-CD set Arkology (Universal/Island) attempts to document the breadth of the work done at Black Ark between 1975 and 1979. Things start grandly with “Dub Revolution Part 1,” an Upsetters dub complete with drum machine, Perry’s mouth noises, and some well-meaning “na na na” vocals that all conspire to sound benevolent, cracked, and cosmically complete. You can even hear mixing desk buttons click on and off as Perry mutes and unmutes the rhythm track toward the end. After that compilers Trevor Wyatt, Steve Barrow, and David Katz opt to make Arkology into Island-ology, fleshing out Island’s out-of-print Scratch on the Wire collection with alternate takes and dubs.

What you get is rich, canonical, juicy, and a bit misrepresentative. Arkology is built around the archivally sound if tedious practice of following each vocal version with its dub or instrumental counterpart, culminating in a numbing six versions of the “Police and Thieves” rhythm. This is instructive for anyone who doesn’t understand that rhythms in reggae music are used many different times by many different artists, though stating such a fact in the liner notes plus one or two examples on CD would have driven the point home. Believe me, you can live without “Magic Touch,” which is Glen DaCosta soloing on saxophone over the length of “Police and Thieves.” And the Island-funded Perry productions Arkology cuts its firewood from—The Heptones’ Party Time, Max Romeo’s War Inna Babylon, Junior Murvin’s Police and Thieves, and Jah Lion’s Columbia Colly—still work well as their own freestanding albums.

More egregiously, Arkology has audio deficiencies: unacceptable digital-master resolution (a sibilant tinniness, like a voice traveling through an aluminum tube) puts the whammy on tunes like “Tedious,” “Bird in Hand,” “Soul Fire,” and “Curly Locks.” This makes me doubly mad because the VP issues of Roast Fish and Return of the Super Ape, taken straight from vinyl with the tone arm audibly bumping over divots, sound better than this allegedly more legitimate release.

I’m not always such an audio geek, but when the meaning of a work consists of the spirit in the sound, the cardiac frequencies of the beat, it’s time to get the ones and zeros straight. If we can bounce a 4 x 4 all over Mars, by god, we can make available a decent CD version of Scratch’s back catalogue. I can’t think of another Black artist this major whose key works remain either out of print or available only in mildly legitimate licensed versions.

There are two other recent Scratch releases. Upsetter in Dub (Heartbeat) compiles B-sides from Perry’s Black Ark era and before (at Randy’s studio17), the latter comparatively light on extreme dub moves, tending to skank rather than splatter. The highlights are the Black Uhuru-ish vocal dub of “Son of the Black Ark,” which threatens to burn down Babylon (but in a nice way), and the churchly, vertiginous “Rejoice in Skank,” blessed with the overheated hovercraft stink that distinguishes good dub from boring instrumentals.

Technomajikal (ROIR) shows the Perry who, since 1980, has become the Orson Welles of dub, pimping out his catalytic presence and wild vocals to voiceover a variety of backing tracks created by admirers. Dieter Meier, once of Yello, provides, like, techno dub, in alliance with X-Perry-Mental (Lukas Bernays and Jean-not Steck), while Perry lays over compudelic toasts in what sounds like a good hour in a Zurich studio on someone else’s tab.

The Beastie Boys’ devoted and informed championing of Perry in Grand Royal two years ago is probably responsible for some of this new spate of Perry product; it’s also easy to observe Perry’s spirit inhering in musicians who have, consciously or not, channeled it, like Tricky, who sounds like Perry with his claustrophobic beats, persecution rhymes, oblique female voices, and fondness for other people’s lyrics, or the RZA, who produces like Perry: quickly, and with no regard for harmony or hygiene, a taste for pop tunes sung badly, and an eye to releasing records on every label in the world. The garden of the Ark continues to grow, a harbor for infinite capacity.