I signed up to work for the census in February. I was finishing the coursework necessary to become an accredited substance abuse counselor (a CASAC-T, in the argot). The training took place at a resource center on Battery Place called Exponents, mostly in one overlit conference room. About thirty people were in class that day, and three of us were transcribing the tiny, crooked type on a Xeroxed sheet taped to the wall. Writing out a URL character by character felt like an admission of defeat.

“I’m already doing it!” one woman told us. “Twenty-eight bucks an hour!”

Twenty-eight an hour is real money, pandemic or no, but my colleague was not already doing it. The census was not on foot yet. The Bureau started their count by sending out emails and postcards to the countable. The idea was that, after this phase, a wave of Non-Response Follow-Up (NRFU) enumerators would hit the street and go door-to-door to reach the reluctant. NRFUs were supposed to start working on April 1st, but they didn’t. April 7th was when my phone rang. Every lockdown call felt like an astronaut at the porthole.

A man named Chris asked if I still wanted to be a census enumerator. I needed the work. I’d only worked as an unpaid intern counselor for two weeks before lockdown. I took urine toxicologies, signed out clients, and did room runs. (A clean room could win a client movie tickets.) It’s an environment that made the transmission of germs and viruses likely, though the facility was free of COVID-19 on March 11. That’s when the director told the unpaid interns to go home. Soon after, the facility laid off a chunk of its workforce. The prospects of being a CASAC-T were not strong.

“I would love to help you count people, Chris,” I said.

Who knows what’s up with this astronaut? Maybe he has it worse.

I received a few calls after that, each gauging my willingness. The reasons to lose interest seemed obvious. Who wants to go around knocking on doors? Who wants to remind anyone of the cops or ICE? We’re all viral threats without the added overlay of state violence. Imagine being invited indoors by someone whose trust you’d just gained and your only two choices are to be a danger, or in danger.

Dan Bouk is associate professor of history at Colgate University and he’s working on a book about the census. I asked him how he would explain the situation to someone in fifteen seconds or less.

“I’d say something like, ‘If you’re not counted in the census, then you might not have somebody representing you.’”

“What if people who don’t feel represented don’t want the government knowing anything about them?”

“The fights around documentation make it hard to make the case sometimes,” Dan said. “I would try to be concrete. ‘What’s the the thing you like about your community the most?’ More than half of those things are related to funding that the Census affects. The library gets the funding it deserves when you’re counted. Don’t want to die of COVID? Then fill out the census. That’s one of the only ways to guarantee enough support for health care in your community.”

I asked Dan about the reports that the census bureau was, counter-intuitively, going to wrap up counting at the end of September, a month early.

“Congress has to extend the deadline,” Dan tells me. “It’s always Congress’s responsibility to apportion itself and it’s supposed to do it by population, according to the Constitution. It’s been almost one hundred years of the process being somewhat automatic, but that automatic system has hit a bump.”

At the end of July, I was told to report for training at 26 Federal Plaza. It’s the only office building I’ve been inside since March, and I’d already been there in June for the fingerprinting phase of the background check. Federal Plaza either faces Foley Square or is Foley Square, I can’t tell which. The square is now the site of a dizzying and fantastic Black Lives Matter mural—word mural? typographic mural?—whose letters stretch north for three blocks alongside the east side of the square. The entrance to 26 Federal Plaza is reached through a long white tent, as if a stray flap of fashion week attached itself to the U.S. government during lockdown. Visitors go through a maze of scanners and x-ray conveyor belts. Once inside the lobby, you see prime Seventies stone with metal detailing, all of it open and visually clean.

On the sixth floor, two lines of enumerators-to-be stretched from one side of the floor to the other. Without uniforms but with masks, state employees could only be identified by their lanyards, which were not generally visible.

“Six feet!” was the instruction, and everyone more or less obeyed it. One woman had lowered her mask beneath her nose but she was the lone rogue. The droplet risk seemed low.

Once in a conference room, we sat spaced out at long tables while three men yelled at us. The training did not include any actual training. We were told how to fill out some forms, including the transmission of our bank information. (This is generally called on-boarding, a phrase that appeared nowhere in the emails we received.) The most important things to remember were apparently our region name (Manhattan South) and our office code (redacted). Before 3 PM, a man named Mario made it clear that we would be leaving at 2:45. A woman came over and asked if I had any questions.

“What are we doing for safety?”

“Your supervisor is going to talk to you about that.”

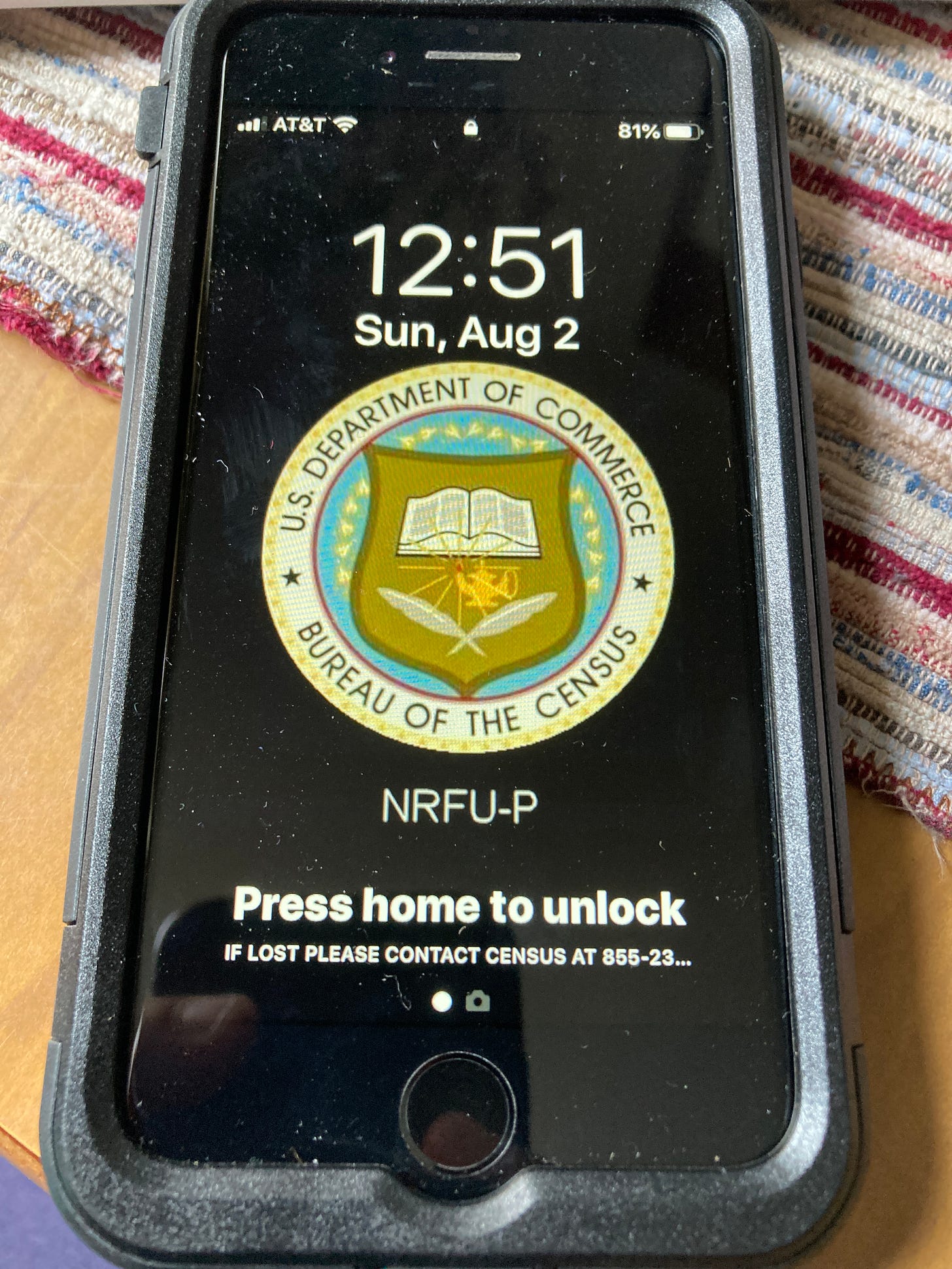

Our supervisors did not talk to us about that. After we signed the forms, we were assigned iPhones.

“You can keep the headphones. We don’t want those back.”

We were given big soft black nylon attaché cases full of tearaway pads, information sheets to give respondents at the start of visits. One piece of the paperwork tells me that the Census Bureau is part of the U.S. Department of Commerce. This made more sense in 1902 when the Department contained both Commerce and Labor. When the division split in 1913, the Census went with the Department of Commerce.

“The Census Bureau counts lot of things other than people,” Dan told me. “There’s a census of mines, a census of agricultural products. They’re mostly economic statistics. The Department of Labor does labor statistics, which is not what the Census does, although labor statistics feel more directly related to the population census than, say, the number of silos in any given state.”

But agencies are not being allowed to do their jobs. Look at the CDC currently dodging the Trump administration’s drunken blows, posting and then un-posting guidelines which they may or may not have written. The functions of the state and the role of the individual are being swept into a massive dust devil of ego that only admits administrative functions if they serve a symbolic purpose for Trump. If the Census can be manipulated to exclude those who wouldn’t vote for Trump, it will be. And for those trying to actually carry out the Census in a time of COVID-19, it’s a game of personal Trick or Treat. COVID barely exists for the administration, and without guidelines from the top, the Census Bureau is trying protect its workers without knowing what that means. All of the morality that could be flowing from the top down is missing, leaving a dry stalk of command. It is now the person at the end of the flow—the enumerator—who has to improvise morality as they see fit. Risk your life to count the population, to vote, to do anything we’d rather you didn’t do. It’s the clearest message of all. Die if you like—you signed the NDA.

As the enumerator training was ending, someone in the room yelled, “When you get home, plug in your phone and don’t turn it off.” Another man came in and told the crew it was 2:45. Mario looked at my phone, trying to help me think of the perfect password. He changed his mind.

“OK, you can do this later. Now go home.”

Nothing census-related happened that night or on the weekend. On the following Monday, at 5 PM, a woman named Denise called me on my batphone. It was startling to hear a new phone in an apartment that hadn’t heard a new native sound in months.

“Hello, Alexander! Do you have NRFU form D-626.2?”

“No.”

Big sigh. “Welcome to the census.”

Over the course of half an hour, it emerged that I should have been doing the self-training all along, using an app on my phone.

“They were supposed to tell you to do it over the weekend. You should be almost done. Well, do what you can do. We had to hire twice as many people as usual because so many people left town in March. It’s all compressed now. I had to learn your job as well as mine, and I had half as long to do it. There’s a lot to get done.”

“How do we get trained?”

“Everything is in your phone. Also, remember to log your hours as work done between 9 AM and 6 PM. Some of the kids, I’m sorry to call them that, but they do their training at 2 AM. Write your hours down between 9 and 6, that’s how they like it.”

“What about safety and COVID?”

“They take it very seriously. It’s in the app.”

All of our PPE fit in a sandwich-sized Ziploc bag. We got two white cotton masks (very comfortable but not big enough for my pumpkin head) and what could be fairly called hipster disinfectant. It’s a four-ounce bottle of hand sanitizer, courtesy of “New View Oklahoma in collaboration with Prairie Wolf Distillery.” A collab in the census bag! And it smells exactly like vodka.

That week, a New York Times editorial detailed Trump’s efforts to curtail the Census. One researcher apparently reported that, in the 2015 fiscal year, for every person missed by the 2010 census, “that person’s state lost about $1,091 in federal funding for Medicaid and child welfare programs.” My duty to help other citizens was clear but little else was. It didn’t seem like anybody was as worried about the pandemic as they should have been, and the people I spoke to at the Census Bureau never used Trump’s name. Their phrase tends to be “the Federal government,” a branch they are part of and which they also blame for all delays and dysfunction.

Then, my Census Field Supervisor, Greg, called me.

“I’m your CFS,” he said. “Make sure to log your hours in the app. I don’t know about the virus. I might have to go out in a mask, maybe a face shield. I don’t know.”

We were not given face shields.

The training took place in the app, and also with browser-based training films and quizzes. If you’ve ever had to become a court-mandated reporter for psychiatric or social work—it’s like that. Slightly obvious and terrifying in its mundane handling of dangerous situations. All of the training videos, though, were filmed in suburban settings, places where you could approach a free-standing house with one entrance and, putatively, stand six feet away from the entrance and remain outdoors. That might work on, say, Charlotte Street in the South Bronx, but it’s not the case anywhere in the East Village, where I live and would be working. Nobody in the videos was wearing a mask and none of the scenarios happened inside apartment buildings. Some warnings were much harsher than other warnings and completely contradicted the implied message that virus transmission was not aggressive.

“Don’t give an information sheet to another respondent after one respondent has touched it,” we were told. This makes COVID-19 sound roughly as contagious as it feels, though we know the virus isn’t generally spread by fomites like paper. I felt like I needed more information. I called Greg back and got bumped up to Bob, another supervisor. I told him the training wasn’t really working, especially because we couldn’t ask questions in the moment.

“Well, we were going to do the training in person, over five days,” Bob told me. “That’s how we usually do it, but the feds thought that was too dangerous so this is how we’re doing it now.”

So it was too dangerous to train us face-to-face and supervisors won’t go out without face shields but we are good to go with our little cotton masks and some kind of realpolitik vibe. OK.

“I’m 66 years old, I have every pre-exisiting condition and I was in the Air Force, and if there’s one thing I know, it’s that you can prepare to meet danger. Then you’re prepared!”

The combination of denial and fear and circular thinking and confusion seemed to be the weather of this in-between zone, between the federal government and the street. To work is to imagine that the neglect and indirect abuse are not coming from above, intentionally, but have happened magically and naturally, like spores. Like a virus.

New York had become the South Korea of America, driving the numbers down to a near-silent rumble and not triggering a new spike. But we know the spikes happen indoors, where lots of people are. Like in a hospital, or a rehab facility—or an apartment building. I didn’t want to be the guy who sparked a new infection by touring the apartment blocks of the East Village, and I simultaneously felt badly, like I was letting everyone down. Greg and Bob have no choice.

I called Greg back and told him my fears. He was a total sweetheart and didn’t pressure me.

“I get it,” he said. “You have to protect your family and do what you gotta do. But you should resign now, because it’s only gonna get worse, not better. We’re not going to get a vaccine next week.”

I asked him about the new deadline, which sounded impossible to pull off in any environment, never mind a pandemic.

“October 31st was our deadline and they just changed it to September 30th,” Greg said. “There will probably be an extension, because there has to be. Nothing went smoothly— training the supervisors, training the enumerators. None of it.”

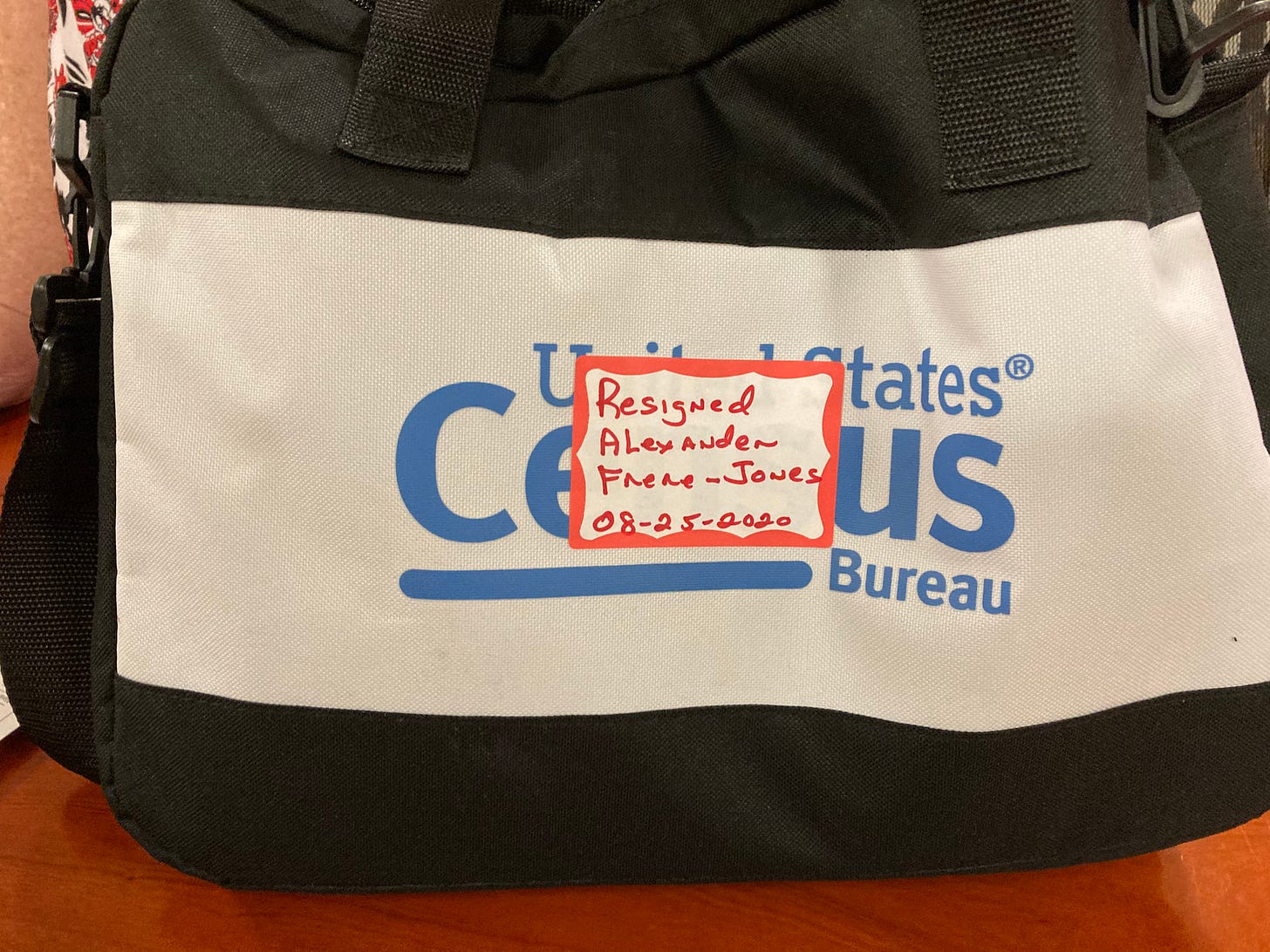

On Wednesday, 15 of my 25 training hours were credited to my bank at $348. On Friday, I formally resigned and Greg texted me the instructions for returning my census gear.

“No problem. I completely understand. You will need to bring your census phone, badge, and bag w/supplies to 26 Federal Plaza, 6th floor. You need to do this tomorrow between 11 am and 2 pm. You need to write or type a letter of resignation stating your name, position, and the date. You do not need to state a reason for resigning. When you get there, you will be asked to fill out a Form D-291. You need to get the name of the person who assisted you, and then you need to text me from your personal phone to let me know that you took care of this. So please have my Census phone number in your personal phone. There are no hard feelings. I respect your decision.”

That same day, the rehab facility emailed me their new back-to-work guidelines. They are “unpausing.”

I haven’t been asked to return because I told them in July that I couldn’t come back on an unpaid basis and I didn’t want to work anywhere without some kind of coherent COVID-19 response. They said they couldn’t pay me but might be able to in the future. Their new guidelines are much more concrete and specific than anything the Census Bureau provided. But they have to be. They are in the same building as their clients, a place where the federal government feels very, very far away.