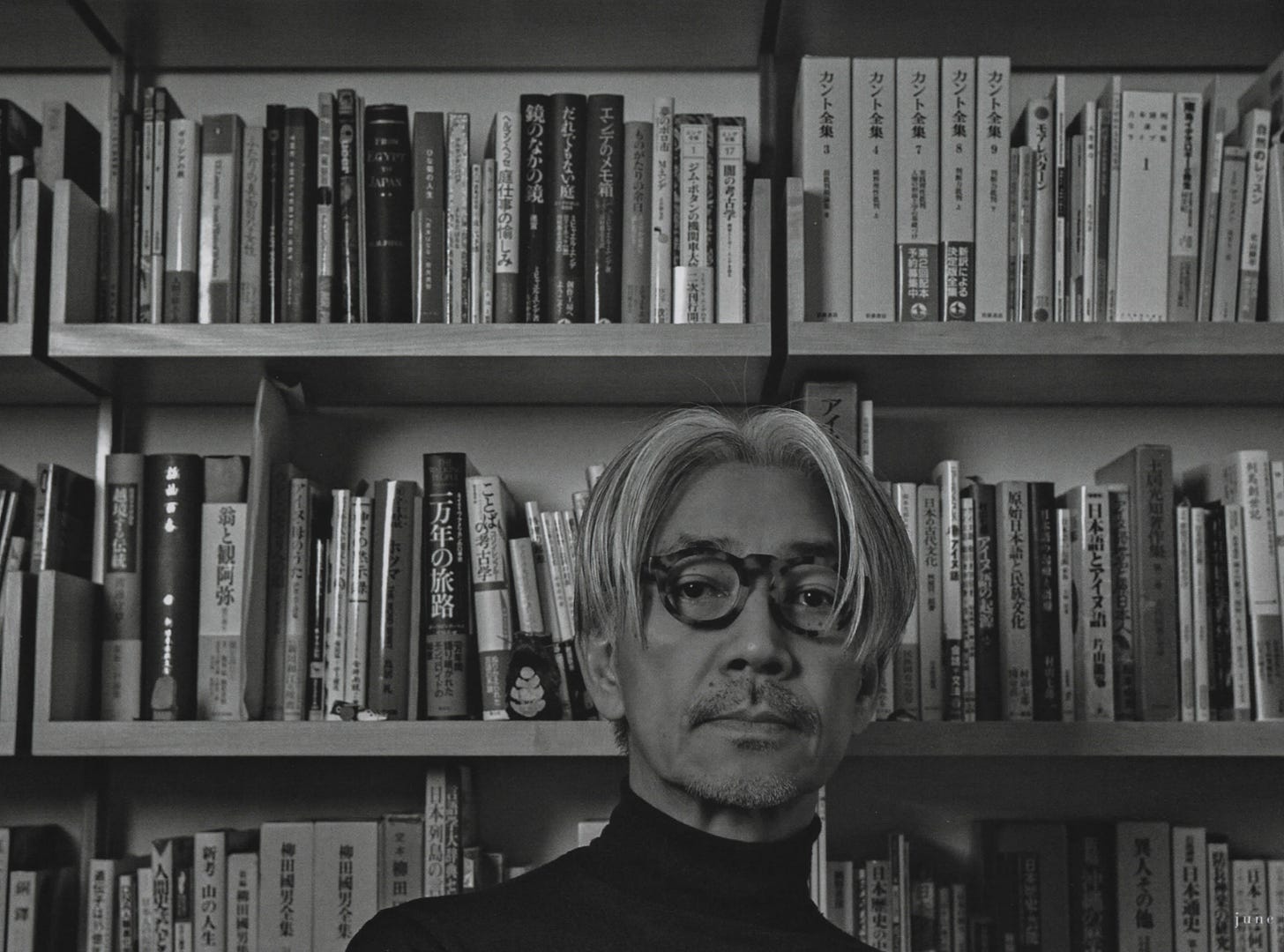

Ryuichi Sakamoto 1952-2023

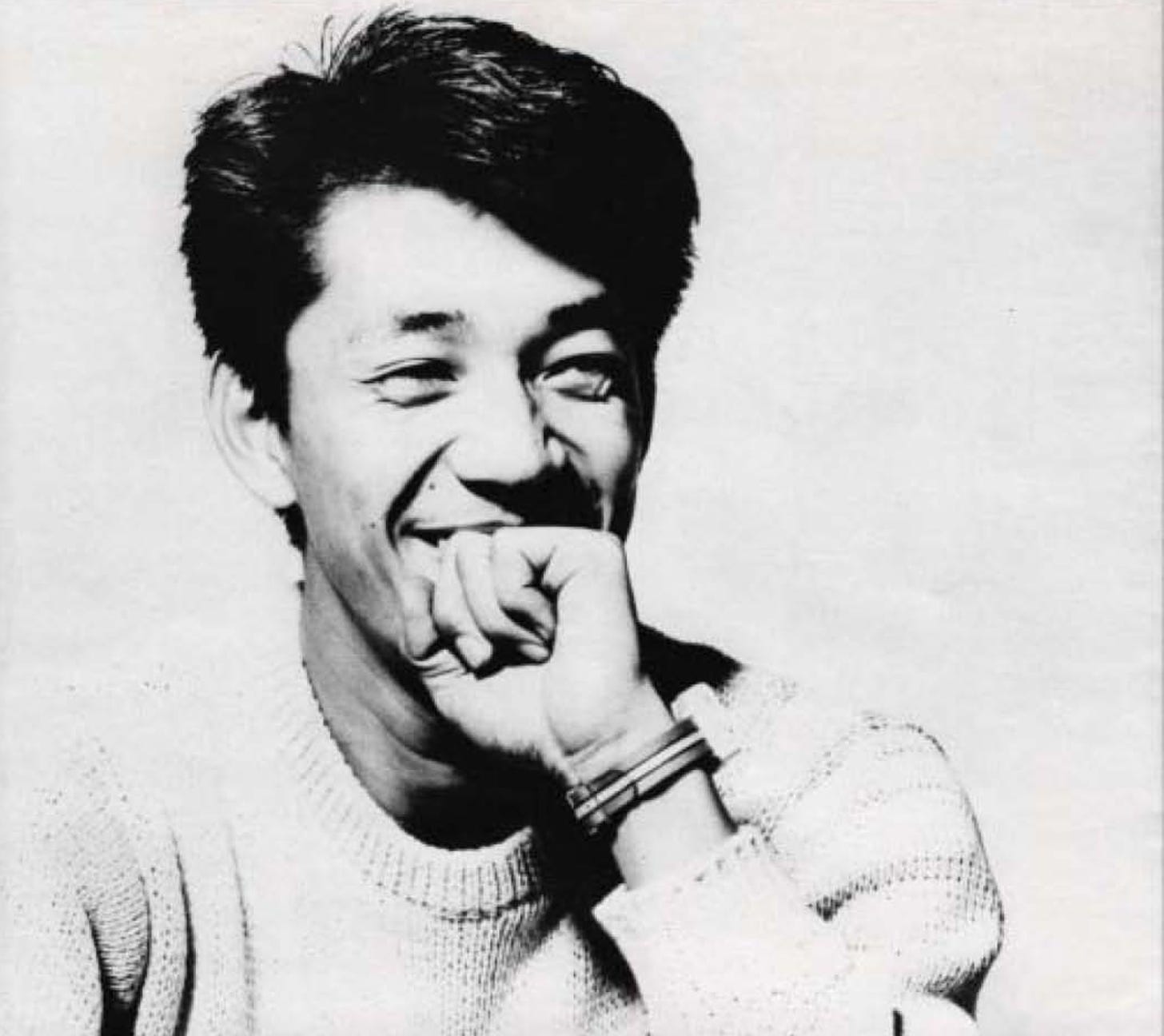

Ryuichi Sakamoto died at the age of 71 on March 28th, 2023, after fighting colorectal cancer for almost three years. For the past few days, I’ve felt anger, demobilizing sadness and watery, imprecise guilt. This is all compounded by losing my own family member to cancer, which is both irrelevant and an accelerant. My feelings around Ryuichi, puckering and childish, are the result of not getting to know him better. He was one of the three or four most remarkable people I’ve ever met. He sensed and thought in a way that most cannot. His gentle voice and piercing stare are often present at the edge of my thoughts. Any time I hear the rustle of seashells, I think of the gear he used to capture outdoor sounds. I still use the small portable mic he told me to buy.

My secondary agitation comes because I was involved in two projects about Sakamoto that both unfolded and collapsed in the last twelve months. I wish I had kept interviewing him regardless of the outcomes, though I have no faith that he would have gone along with that. He was practical. Sakamoto put out an album (a great one) and a concert film (valuable in a different way) in the course of the last twelve months, and distractions with no concrete end would likely have not appealed to him. (Ryuichi describes here how the concert film was pieced together, one song at a time, indicating both his seriousness and the degree to which the disease had weakened him.) When one of the two projects, a magazine feature, went from a yellow light back to red, the editor said Ryuichi was the musician’s equivalent of “a writer’s writer,” which was reason enough for a general interest publication to say no. Though this verdict frustrated me, I don’t think it was necessarily wrong, or even a value judgment.

His career is confusing, sometimes in many ways at once. Though the NYT obit describes his theme for the 1983 film, Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, as “synth-heavy,” it was only rendered that way in the original recording. Sakamoto was primarily a pianist, describing himself as such, and “Mr. Lawrence” became the centerpiece of his solo piano concerts over the years. And though this is true, and he often cited Debussy as an inspiration, these facts do not do much to illuminate his electronic collaborations over the last two decades, several with Carsten Nicolai aka Alva Noto. Some of those have a sere crispiness, maybe related to his practice of field recording things like melting icebergs, or are possibly just another manifestation of his ability to appreciate how everything sounds, including the mechanical. He told me that the innate sonic qualities of a thing are always a good place to start, whether or not any of it seems musical at first.

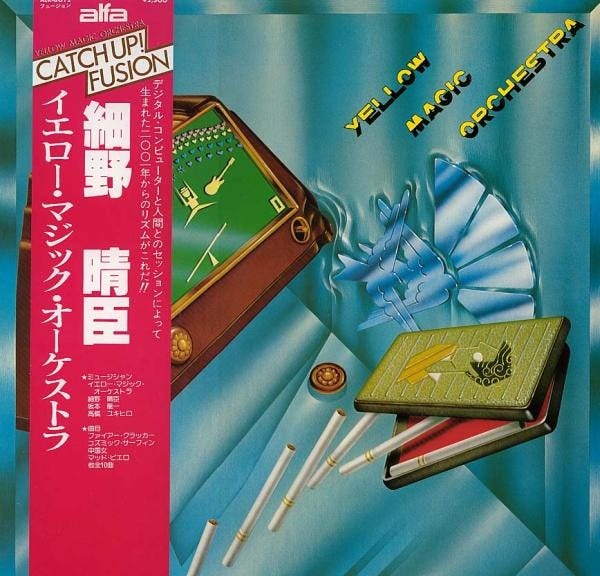

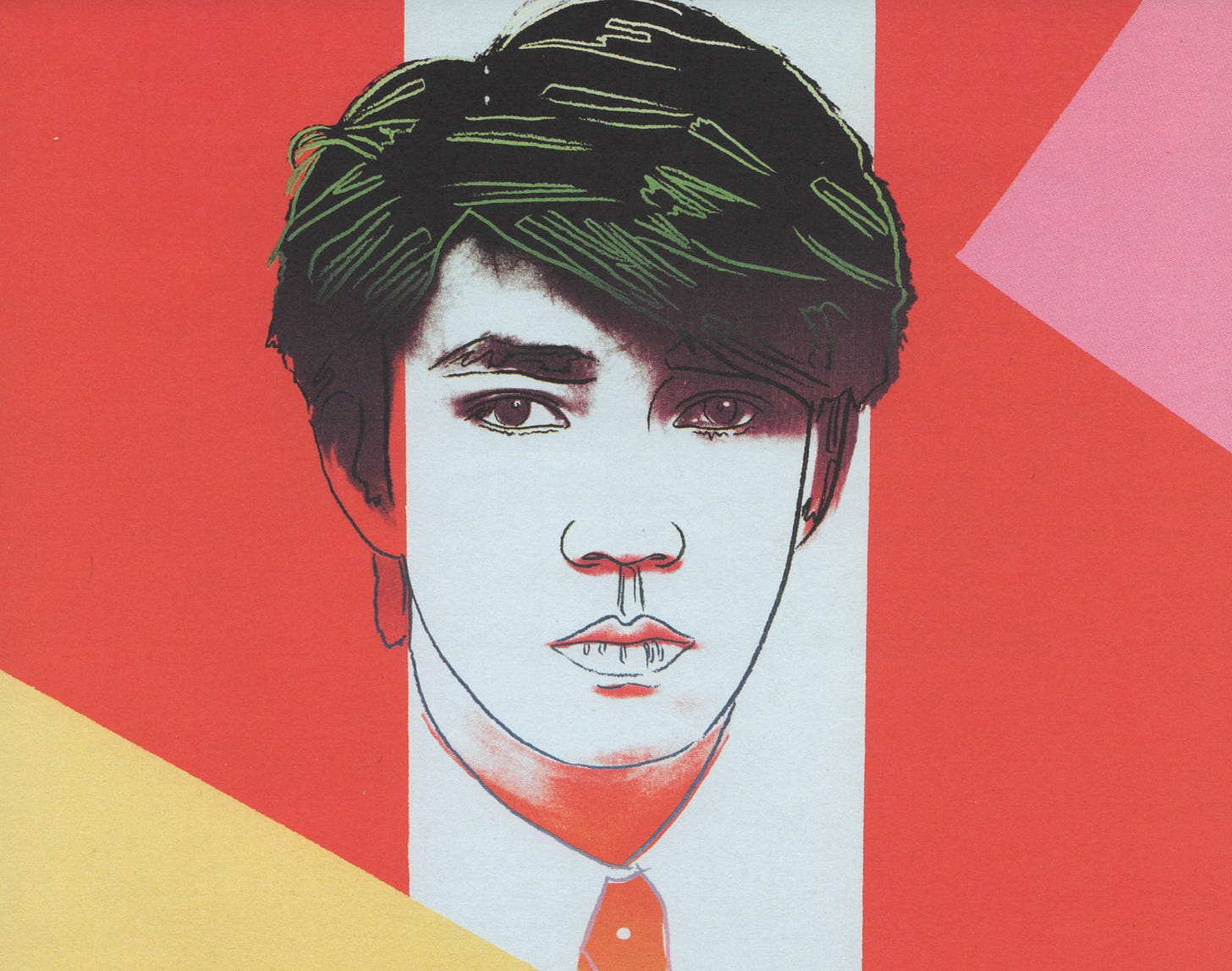

His career happened outside America, largely, and the English language press only decided to cover it sporadically. Synthesizers are how the world first got to know Sakamoto and his first big chart hit in that vein defines the idea of confusion. There is no short version of this but I will lop off some of the branches. Yellow Magic Orchestra, a name that plays on racist stereotypes, was the Tokyo band started by Harumi Hosono as a studio project in 1978, initially with modest expectations. A song on their first album was a cover of Martin Denny’s “Firecracker,” an Orientalist fake from the Fifties that ended up signifying Asian-ness in cartoons and films. Sakamoto, a piano prodigy doing sessions all over the place, ended up in Y.M.O., a band that unexpectedly ended up being superstars off the success of “Firecracker” and the first LP. Things got weird when the song became a single in the US called “Computer Game (Theme from The Circus).” This is what your correspondent, as a 12-year-old, bought. It looked like this. That title actually corresponds to the first song on the YMO album, a brief lead-in for “Firecracker.” A translation error? Probably. Someone at A&M was handed the album and maybe couldn’t sort it out, since “Computer Game” and “Firecracker” do have the same rhythm track and blend into each other. So the label doesn’t even mention Martin Denny in the songwriting credits of the US single, and my young self just thought the whole thing had to do with video games. I was accidentally hip enough to buy the single but didn’t much like it, not that understanding what it was parodying would have made any sense to me. The Times obit correctly notes that YMO were “satirizing Western ideas of Japanese music” but still calls the single “Computer Game.” Finicky nerd shit? I posit this: hell no. Had the younger crit community known what they were dealing with—and yes, some recognized the Denny tune—I think this would have been a much bigger deal in terms of race and music and detournément and all those popular Eighties tropes. Was “Firecracker” the Japanese version of “Say It Loud (I’m Black And I’m Proud)”? No, but it wasn’t entirely not that. I mean, we ended up with The Vapors’ “Turning Japanese” the following year, doing all of the worst possible things with the same ideas and musical clichés. Sad!

Sixteen-year-old me bought a very important and terrible record called Death Mix in 1983, an early live rap mix that is credited to Afrika Bambaata, Jazzy Jay, and Afrika Islam, though consensus says Jay did the actual mixing. You’ll hear “Computer Game” pop up in that excerpt and I will be honest, I didn’t like it the second time around either. Still too fast! In the subsequent decades, I managed to miss Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence and most of Sakamoto’s solo output. I knew he collaborated with David Sylvian and saw his name on the Alva Noto collaborations but I never followed up with it or gave him much thought. I was embarrassingly late to the Sakamoto game and only really felt the penny drop when I heard async in 2017. That drop was hard. Should I exaggerate? Why not? I think async is maybe one of the ten or twenty great records from the teens, and it is only improving. Sakamoto’s sense of space is a way of acknowledging resonance, a quality that leads him to his beloved scrapes and whines and crunches, some of which do not even sustain for a moment, which makes sense for someone obsessed with the idea of sustain. The melodies and textures and varieties here make this feel like a greatest hits album, which it is not. It was conceived and written after his first diagnosis, in 2014. You can learn about this and more in Stephen Nomura Schible’s fantastic 2018 film, Ryuichi Sakamoto: Coda. If you have any interest in Sakamoto, stop reading and watch that now.

Coda is truly great, as quiet and un-neurotic as Sakamoto’s music. Chunks of async’s making are represented here, like the clip of Paul Bowles, from The Sheltering Sky, that ends up on “fullmoon,” with Sakomoto discussing the “collage” he wants to make. There are scenes of him recording the sound of leaves in an unidentified forest and listening to the rain on his skylight in the West Village.

The film begins with his trip through Fukushima. “I heard about a piano that survived the tsunami,” he says at the opening. He finds it, and it can be heard on async. Someone who was present for the tsunami describes it to Sakamoto as “a black wall of water,” which comes back years later in his theater piece, TIME, staged in an actual black sheet of water. In Coda, the geiger counter almost immediately feels like it is taking readings of both Fukushima and Sakamoto, who discovered he had stage 3 throat cancer in July of 2014. “I couldn’t come to terms with it,” he says, seeming very much to have come to terms with it. In the opening of Coda, he plays “Mr. Lawrence” for an auditorium of families in a junior high school that was used as an evacuation site during the original meltdown. You see him working on the score for The Revenant, and simultaneously working on async (calling “stakra” “very 80s” as it plays in his studio). This was his version of taking it easy while ill.

Ryuichi and I finally met in July of 2018, when Danny Kasman of Mubi asked me to interview him in front of a live audience, after a screening of Coda at Lincoln Center. When I first saw him in the green room, his manager Norika Sora was sitting with him. We shook hands and the first thing Ryuichi said was, “I like your photographs.” He was holding a book of Tarkovsky’s Polaroids. I was, at first, flushed with ego juice and thrilled the maestro liked my work. But why had he bothered? He had little reason to look me up, much less find my photographs and tell me what he thought of them. If it was a strategy, it was perfect. I don’t think it was.

On two consecutive nights, we did brief talks after screenings of Coda. He was as careful and charming as I expected him to be. When an audience member asked if he got tired of playing “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence” in concert, Ryuichi talked about seeing Carly Simon in person, years ago. He had been enjoying himself but feeling vaguely unfulfilled until James Taylor came out for the encore and did “You’ve Got A Friend” with Simon. “Finally, I was happy,” Ryuichi said. After that, he never felt funny about playing “Mr. Lawrence” when asked to. Everyone wants the hits.

After the second screening, we agreed to get dinner, and made a date for a place called Kokage, on Sunday night, July 22, 2018. The restaurant was not listed on the web (at least then) but its upstairs component, a sushi restaurant called Kajitsu, was. The dinner was exquisite, and the only odd moment was when Ryuichi got up to tell someone to adjust the volume on the music. His tone felt bossy, an approach that didn’t seem like him. He did not explain the situation, but surreally, the next morning, a piece in The New York Times reported that the music we had been hearing was a playlist he had made for the restaurant. Uncannily, the playlist features none of his own music but all of it sounds like him.

Ryuichi and I began corresponding lightly and then got coffee one morning in August of 2018, near his West Village home. He kept his iPhone in an attractive leather wallet. It occurred to me he likely didn’t have any inelegant possessions. I asked him how he recorded environmental sounds and he showed me the portable Shure microphone you see with its wind filter—the little foam afro—in Coda. We talked about trees and how we think of sound. Ryuichi thought that no music could be as good as a tree. I said I wanted to make records again but was nervous because it had been almost ten years since I’d been in the studio. How does one make a good record?

“Make a bad record,” he said, and laughed. “I do it all the time.”

It was easy and comfortable to talk with him, and his curiosity for everything was apparent. I did not know if I wanted to make music that he would like or if I wanted to make music I could discuss with him. After that coffee, we kept emailing but didn’t see each other again in person. We lost touch for two years and then connected in June of 2021 while I was preparing to write about his theatrical piece, TIME, for Artforum. I knew, at this point, that he was sick again but we didn’t discuss it.

dear sasha,

thank you for writing about TIME.

the theme is ’the conflict between humankind and nature’.

humankind creates a road, time, science, logic, number, a straight line,,,,, which we cannot see those in the nature.

i think we live in the illusion we create.

here is the obvious example. in any ethnic groups of people, they have a constellation of stars.

and the constellation is tied with straight lines as if those stars and on the same plane.

but we know that’s not the reality.

anyway, i have used three stories about dream in TIME.

but the real main story is the man who wants to create a straight road in the water.

obviously, water represents Nature.

the man represents humankind.

does is make sense?

do you understand what i mean?

warmest, Ryuichi

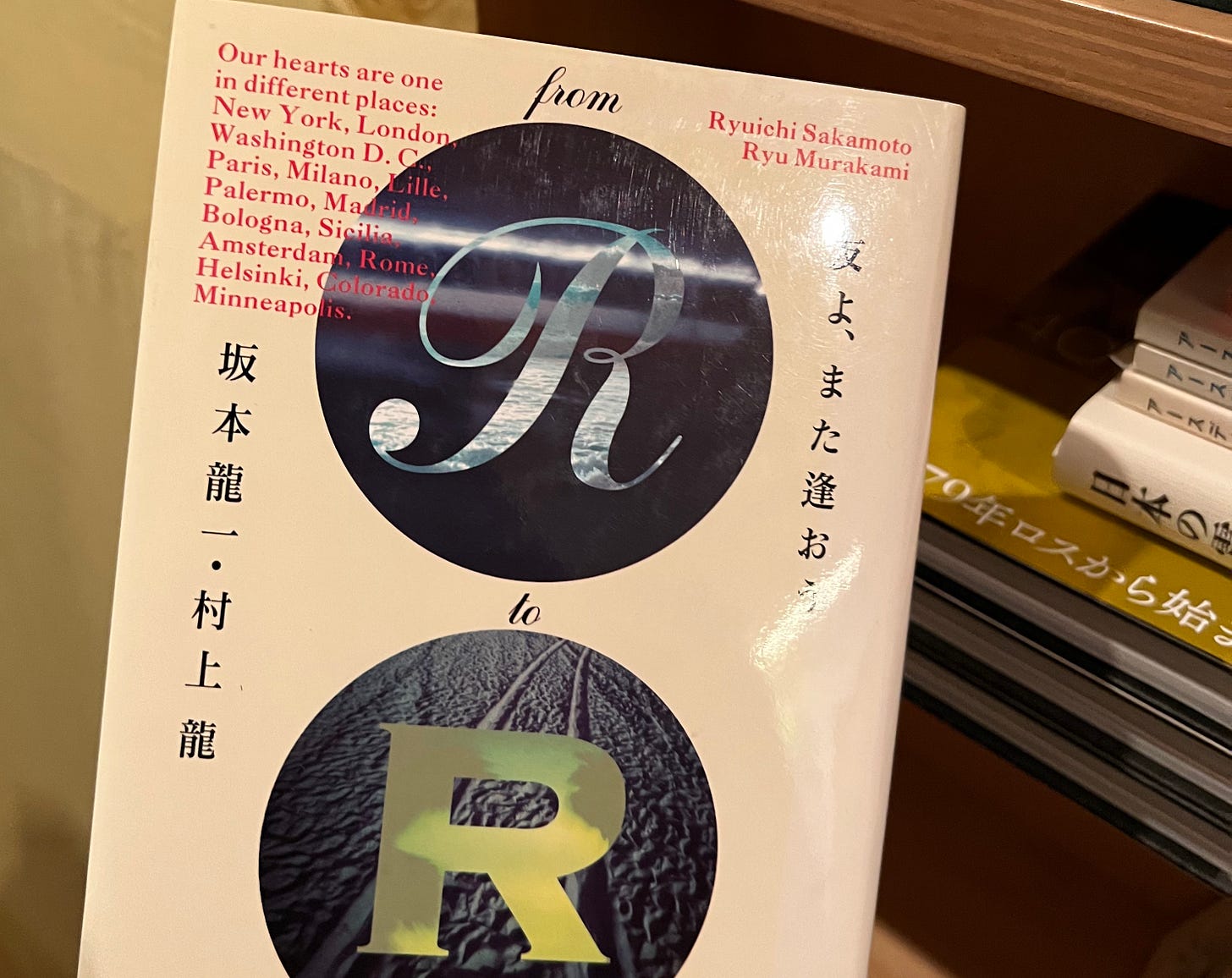

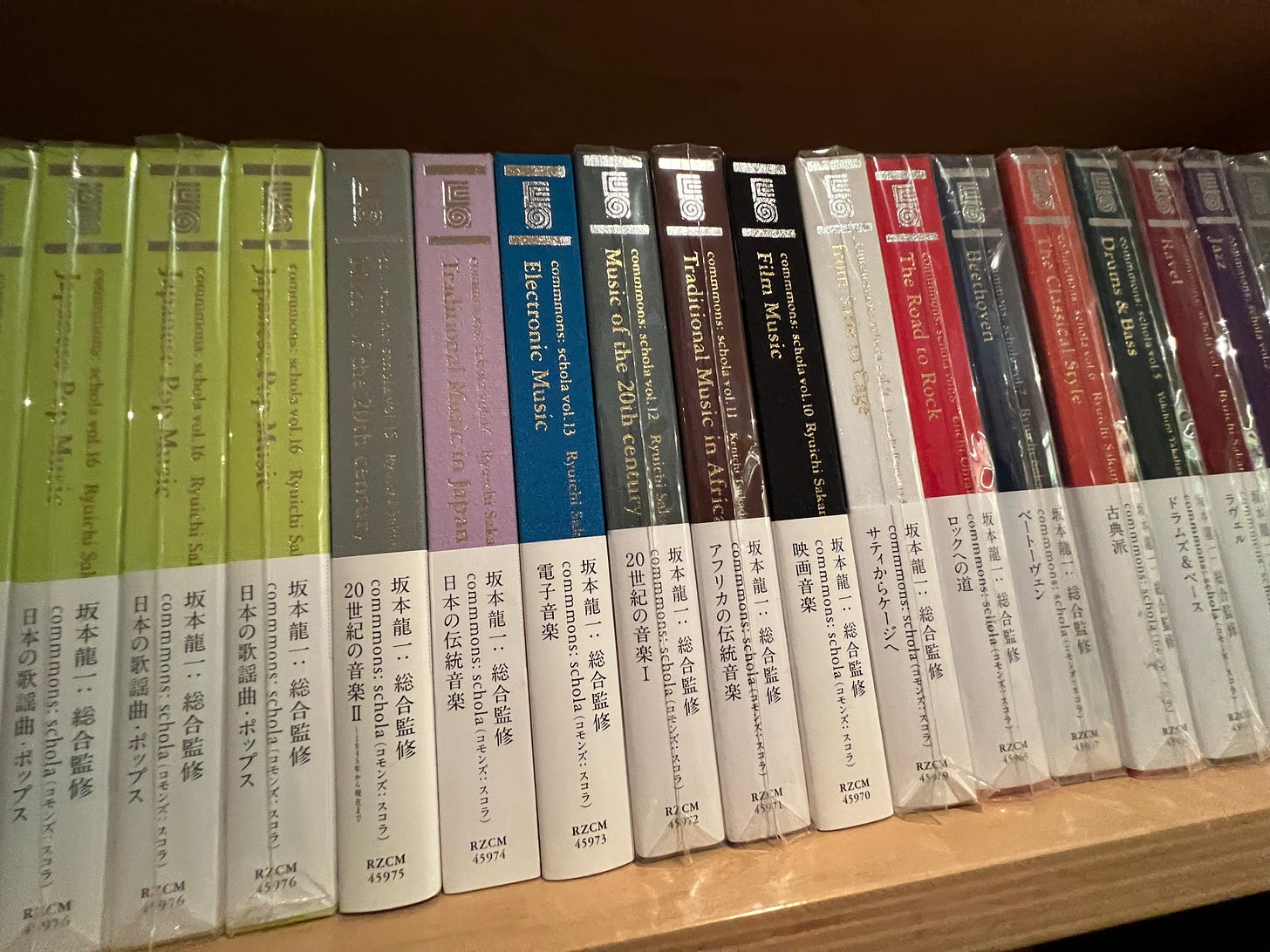

In the summer of 2022, the two projects I mentioned sprang up simultaneously. A small publisher asked me to do a chapter for a book about Ryuichi, and a magazine agreed to run a profile of him, possibly flying me to Tokyo. Ryuichi’s team was still in New York, as the basement of his West Village brownstone was both his studio and his business HQ. The KAB squad, Alec and Maria and Yuichiro, were exceedingly kind to me and shared images and articles from the archive, some of which you see here. Several book-length interviews with Ryuichi exist and at least one of them was put out by a press Sakamoto ran for several years in Japan. He also created something called commmons: schola, a seventeen-volume history of music, which is at least partly annotated in English. There is a playlist of videos on the commmons YouTube channel featuring Sakamoto in a black wig and white lab coat, playing the part of music professor. There are also dozens of other visual projects. Very little of this has been translated into English.

We had a final Zoom call in August of 2022, after Ryuichi had made the decision to stay in Tokyo for the remainder of his treatment. I chattered nervously about how the pieces were coming, and then we shifted into a narrative that began close to the beginning, or as close as I could get it. He told me that when he started shopping for records in the Seventies, he looked for anything that was “unknown, anything unknown.” His first full-length vinyl debut in 1976 was, in fact, a free improv duet. Ryuichi had been committed to out jazz, starting with Coltrane and extending as far as it could go in the Seventies and Eighties. He was close with a saxophone colossus of Japan, Kaoru Abe, and a jazz critic whose name I have not deciphered.

His first trip out of Japan, it turns out, was not to London or New York, but to Jamaica. In 1978, he recorded a wild variety of sessions. (Just look here on Discogs—it’s easy.) Ryuichi said the Jamaican session was for a female singer but could not remember her name. After half an hour, he said he was tired and Norika bid me goodnight, though it was morning there.

Ryuichi Sakamoto represents an alternative view of how a musician can interact with and reflect the world. By that, I do not mean that there is a mainstream narrative that we are subject to and that Ryuichi is the left to that right or the red to that green. Specifically, I think the life Ryuichi lived and the way in which he worked is an example of a creative life with spiritual integrity.

The archive is growing by the day. Here, for instance, are seven videos of Ryuichi with Towa Tei in October of 1994 at Bar Isn’t It in Tokyo, playing keyboards while Towa Tei DJs. Towo Tei, in fact, broke through by sending a tape to Sound Street, Ryuichi’s NHLK radio show, in 1986. This post does a great job of explaining the show, and the demos they received, with links to some of it (though copyright algos are eating more of it everyday). Here is one full show, not from 1981 but 1986. No idea why it’s mislabeled. Or if that seems like too much work, watch this amazing appearance on Club Lotus from 1985. Ryuichi is doing a solo set, alone, in what might be a temple in what is definitely Bali, playing a techno-ish tune that uses gamelan metallophone samples. Shorts! Yellow glasses!

For more general background, I recommend this interview Geeta Dayal conducted with Ryuichi in 2006 and Simon Reynolds’s appreciation in Pitchfork. Anyone unfamiliar with Yellow Magic Orchestra would do well to watch this entire ninety minute compilation, Visual YMO, or this insane concert film, Propaganda, which is like Bonnie Tyler’s “Total Eclipse of the Heart” video but much longer and stranger. Best of all is Tokyo Melody, the Eighties documentary excerpted in Coda. I smile thinking of anyone watching it for the first time.

Something you will find out, though, if you go far enough with Ryuichi’s music, is that he was wrong about one thing and maybe only one: he did not make bad records, not ever.